Supply Chain Problems: Distribution Risks for Generic Drugs

Dec, 25 2025

Dec, 25 2025

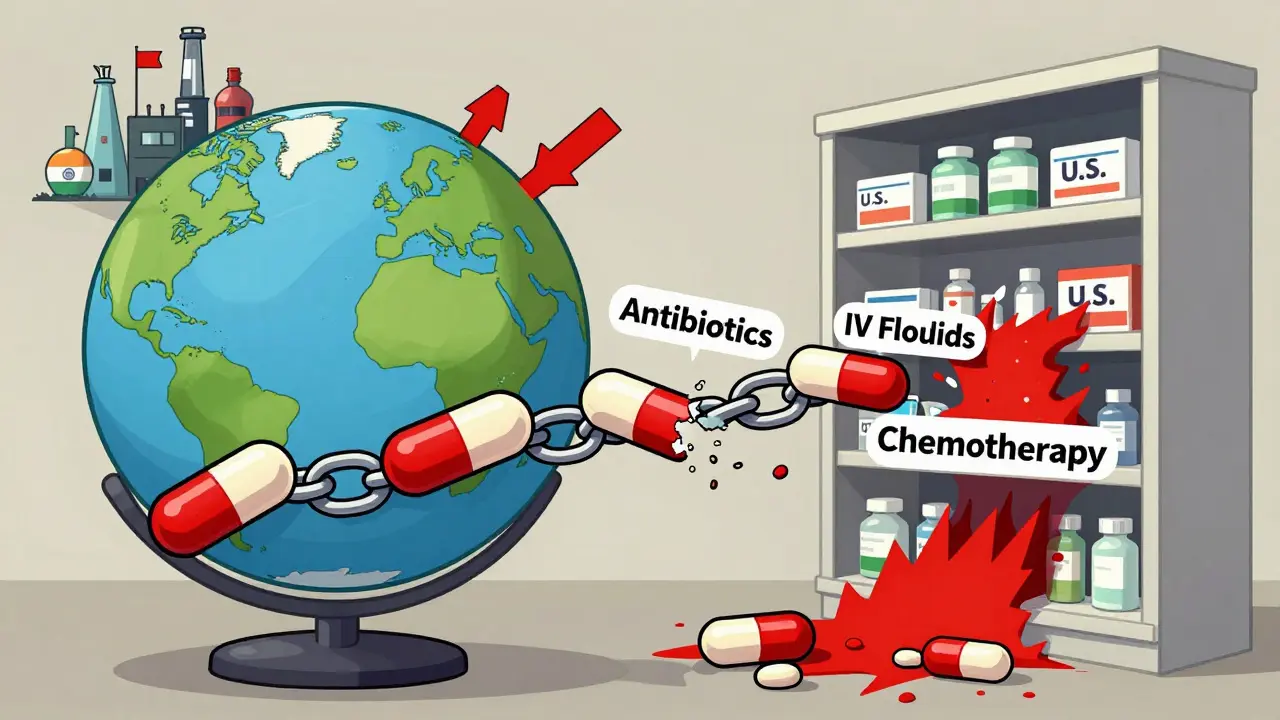

By the end of 2025, over 270 generic drugs were still in short supply across the U.S. - many of them essential, low-cost medicines like antibiotics, IV fluids, and chemotherapy drugs. These aren’t random glitches. They’re symptoms of a broken system built on thin margins, overseas dependence, and fragile manufacturing networks. If you’ve ever waited days for a prescription to be filled, or seen your doctor switch your medication last-minute, you’ve felt the ripple effect of this crisis.

Why Generic Drugs Are the Weakest Link

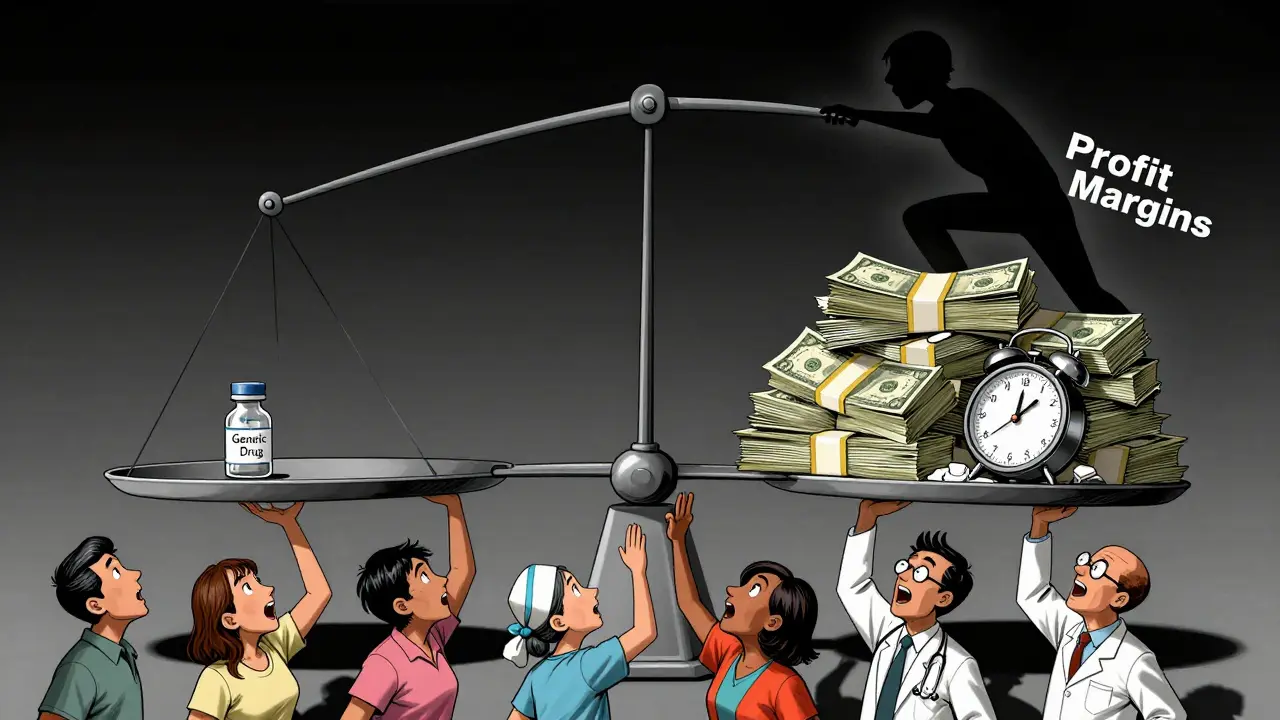

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they account for just 13% of total drug spending. That’s because they’re cheap - sometimes less than $5 per dose. And that’s exactly the problem. Manufacturers can’t afford to stockpile inventory, upgrade equipment, or diversify suppliers when every pill barely covers the cost of making it. Brand-name drug companies, by contrast, have profit margins that let them build backup plans: multiple factories, global sourcing, and buffer stocks. Generic makers don’t. They run on razor-thin returns, often competing on price alone.The Global Bottleneck: Where APIs Come From

The active ingredients in most generic drugs - called APIs - don’t come from local pharmacies. They come from factories in China and India. China supplies about 40% of the world’s APIs. India handles most of the final manufacturing, especially for sterile injectables like heparin, epinephrine, and saline solutions. These aren’t just distant suppliers. They’re the backbone of your medicine cabinet. But this system is dangerously concentrated. If one factory in India has an FDA inspection failure - like the one that shut down cisplatin production in 2023 - the entire country can face a nationwide shortage. If a tornado hits a plant in Kentucky, as it did to Pfizer in 2023, 15 different medications vanish overnight. There’s no backup. No redundancy. Just one source for drugs millions rely on.Sterile Injectables: The Most Vulnerable

Not all generic drugs are equally at risk. Sterile injectables - the liquids you get through an IV - are the most likely to run out. Why? Because making them is hard. They need clean rooms, sterile equipment, and highly trained staff. One speck of dust can ruin a batch. These facilities cost millions to build and maintain. Few companies want to invest in them when the profit per vial is less than the cost of a cup of coffee. The FDA’s own data shows these drugs dominate the shortage list. In 2024, over 60% of active shortages involved injectables. Cancer treatments, antibiotics for sepsis, emergency epinephrine - all of them are at risk. When these drugs disappear, hospitals scramble. Nurses ration doses. Patients wait. Surgeries get canceled. There’s no easy substitute.

Manufacturing Consolidation Creates Single Points of Failure

For many older generic drugs, production has shrunk to just one or two manufacturers. Take doxycycline, a common antibiotic. A decade ago, five companies made it. Now, it’s two. One plant goes down - and the whole country runs out. This isn’t an accident. It’s the result of decades of consolidation. Smaller companies couldn’t survive the price pressure. Bigger ones bought them up and shut down competing lines to cut costs. The result? A supply chain with no safety net. The USP 2025 Annual Drug Shortage Report found that 70% of the most critical shortages involved drugs made by only one or two producers. That’s not efficiency. That’s a ticking time bomb.Why Tariffs Won’t Fix This - and Might Make It Worse

Some politicians push tariffs on Chinese and Indian drug ingredients as a way to force manufacturing back to the U.S. But experts warn this could backfire. A 50% to 200% tariff would raise the cost of APIs overnight. Manufacturers would either raise prices - hurting patients - or cut production. Either way, shortages get worse. The CSIS analysis found that tariffs would disrupt existing supply chains without replacing them. Building a single sterile injectable facility in the U.S. takes five to seven years and $500 million to $1 billion. We don’t have that kind of time or money to rebuild the entire system from scratch. And even if we did, the market still wouldn’t pay enough to keep those factories running.What’s Being Done - and Why It’s Not Enough

There are proposals. The Strategic National Stockpile could be expanded to hold six months’ worth of critical generics. Congress has introduced bills like S.2062 to mandate reserves. Some lawmakers want mandatory labeling to show where APIs come from. Others suggest public-private partnerships to fund domestic production. But progress is slow. Federal agencies like the FDA and HHS have lost staff and funding. Inspections of foreign plants have increased, but domestic oversight has dropped. That creates blind spots. A factory in India might pass inspection one year, then fail the next - and no one in the U.S. knows until the drug vanishes from shelves. Pharmacists spend 20 to 30% of their week just managing shortages - calling other hospitals, compounding drugs by hand, or finding alternatives that aren’t as effective. One hospital pharmacist told Pharmacy Times, “I’ve had to tell a cancer patient we don’t have the drug today. And I had no other option.”

Who Pays the Price?

Patients don’t see the supply chain. They just see their prescription is unavailable. They get delayed cancer treatments. They get weaker antibiotics. They get substituted with drugs that have different side effects - or none at all. Elderly patients on IV fluids miss dialysis. Children with infections go untreated. Clinicians are forced to make life-or-death choices because of a broken system. The problem isn’t just about money. It’s about trust. When a drug you’ve relied on for years suddenly disappears, you start wondering: Is my medicine safe? Will it be there next month? Will my doctor even know what to give me instead?What Needs to Change

There’s no single fix. But real progress needs three things:- Price floors for critical generics - Not subsidies. Not handouts. Just a minimum price that lets manufacturers cover costs and invest in quality. If a drug saves lives, it shouldn’t be sold for less than it costs to make.

- Multi-sourcing requirements - The FDA should require at least two approved manufacturers for every essential generic drug. No more single points of failure.

- Domestic capacity with incentives - The government should offer long-term contracts or tax credits to companies willing to build U.S.-based sterile injectable plants. Not to replace China, but to create redundancy.

Kuldipsinh Rathod

December 26, 2025 AT 17:24This hit home for me. I work in a hospital in Mumbai, and we’ve had to switch antibiotics three times in the last year because the Indian-made generics shipped from China got delayed. No one talks about how this affects patients overseas too.

Matthew Ingersoll

December 28, 2025 AT 01:26The system is designed to fail. Cheap doesn’t mean efficient-it means brittle. And we’re paying for it with lives.

carissa projo

December 29, 2025 AT 06:18It’s heartbreaking to think that the very drugs meant to heal us are treated like commodities on a discount shelf. We’ve outsourced not just manufacturing, but compassion. What if your mother’s chemotherapy vial came from a factory that hadn’t been inspected in 18 months? Would you still call it ‘affordable’? We need to stop measuring value in dollars and start measuring it in survival.

josue robert figueroa salazar

December 29, 2025 AT 09:44One plant down and the whole country panics. That’s not supply chain. That’s Russian roulette with IV bags.

david jackson

December 29, 2025 AT 18:16Think about this: we spend billions on space telescopes and AI chatbots, but when a cancer patient needs a simple saline drip and there’s none left because a factory in Hyderabad had a power outage, we shrug and say ‘it’s just a generic.’ We’ve normalized neglect. We’ve turned medical scarcity into background noise. And now we’re surprised when nurses cry in the break room because they can’t give a child the antibiotic they need? This isn’t about tariffs or trade deals-it’s about whether we still believe life has value beyond a price tag.

Jody Kennedy

December 30, 2025 AT 03:47Let’s stop pretending this is just a ‘pharma problem.’ It’s a human problem. We need to rally like we did for vaccines. This is the next pandemic waiting to happen-quiet, slow, and deadly. We can fix this. We just have to choose to.

christian ebongue

December 31, 2025 AT 23:17Oh cool so now we’re gonna tax APIs and pretend we’re saving jobs? Bro we got one plant in Kentucky making 60% of the epinephrine and you wanna add 200% tariff? That’s not policy thats a meme

jesse chen

January 2, 2026 AT 14:10There’s a quiet heroism in pharmacists who spend half their day playing drug roulette. I’ve seen it. They’re not just filling prescriptions-they’re stitching together a broken system with duct tape and hope. And we don’t even thank them. We just assume the medicine will be there. It shouldn’t take a crisis to make us care.

Joanne Smith

January 3, 2026 AT 01:46Let’s be real: if this were about brand-name cancer drugs costing $10,000 a dose, Congress would have passed a law last Tuesday. But since it’s $3 antibiotics and $5 saline bags? Eh. We’ll just tell patients to ‘try another pharmacy.’ The system doesn’t break-it just lets people fall through.

Prasanthi Kontemukkala

January 4, 2026 AT 12:19My father needed heparin during his last hospital stay. We waited four days. I remember the nurse saying, ‘We’re rationing it now.’ That’s not healthcare. That’s triage. We need to treat these drugs like air-not something you buy on sale.