Sirolimus and Wound Healing: Surgical Complications and Timing

Dec, 4 2025

Dec, 4 2025

Wound Healing Risk Calculator

Patient Risk Assessment

Risk Assessment Results

Enter your information to see personalized risk assessment

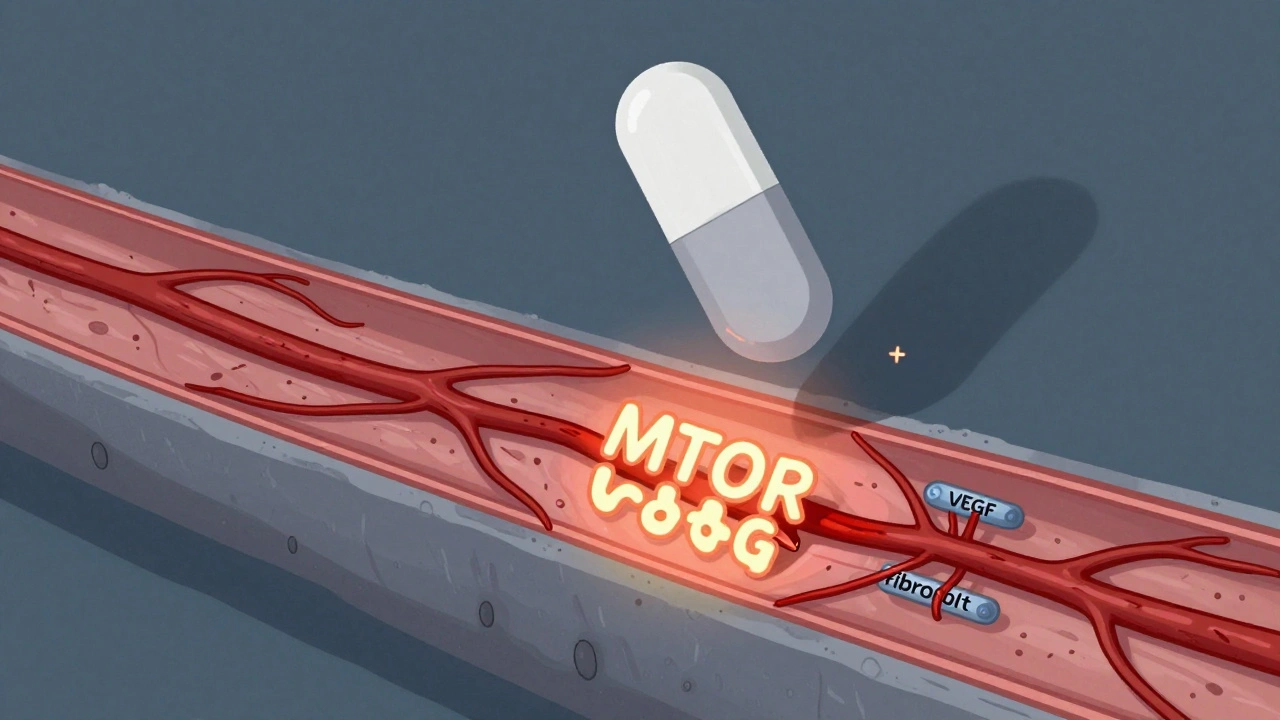

Why Sirolimus Slows Down Wound Healing

Sirolimus, also known as rapamycin, is an immunosuppressant used after organ transplants to stop the body from rejecting the new organ. It works by blocking a protein called mTOR, which controls how cells grow and divide. That’s great for keeping the immune system quiet-but it’s also why healing after surgery gets stuck. When you cut the skin, your body needs to rebuild tissue: blood vessels form, fibroblasts make collagen, and immune cells clean up the area. Sirolimus shuts down most of that process. Studies show it cuts down on VEGF, the signal that tells blood vessels to grow into the wound. No new blood vessels? No oxygen, no nutrients, no healing. It also stops fibroblasts from multiplying and laying down collagen, the scaffolding that holds the wound together. In rat studies, wounds treated with sirolimus had up to 40% less breaking strength than untreated ones. That’s not a small drop-it’s the difference between a wound staying closed and splitting open.

The Real Risk: When Do Complications Happen?

It’s easy to think sirolimus always causes bad wounds, but that’s not true. The risk isn’t the drug alone-it’s when you give it and who you give it to. The biggest danger comes in the first week after surgery. That’s when your body is doing its most intense healing work. If you start sirolimus then, you’re basically hitting pause on recovery. A 2009 review from Frontiers Partnerships found that most transplant centers delay sirolimus until at least day 7, sometimes up to 14 days, just to avoid this window. But here’s the twist: not every patient has the same risk. A 2008 Mayo Clinic study looked at 26 transplant patients on sirolimus who had skin surgeries. Their infection rate was 19.2%, and 7.7% had their wounds split open. That sounds scary-but the control group had only 5.4% infections and zero dehiscence. The difference wasn’t statistically significant. Why? Because the sample was small. But it does hint that maybe the risk isn’t as high as we once thought, especially for minor procedures.

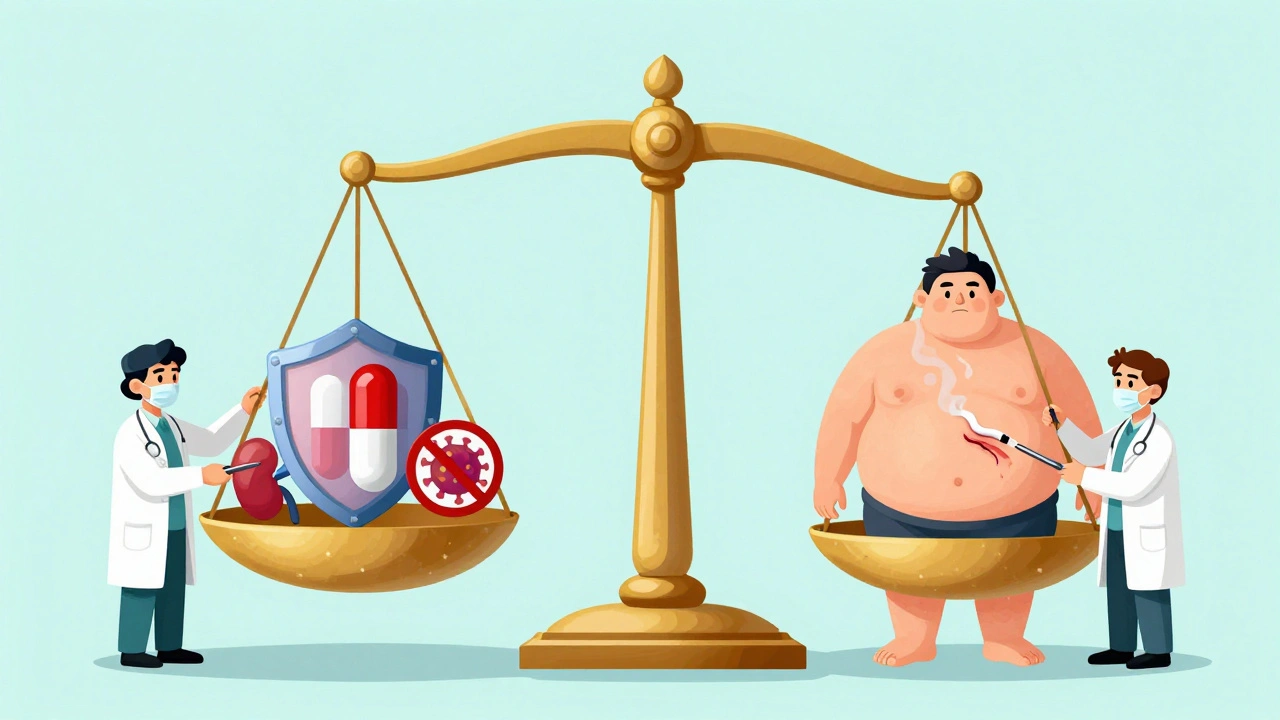

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not all patients are created equal when it comes to healing. The biggest red flag? Body mass index (BMI). Higher BMI means higher odds of wound problems-some studies say the risk doubles or triples. That’s because fat tissue doesn’t heal well, and it’s harder to get good blood flow there. Other big risks include diabetes, smoking, poor nutrition, and chronic kidney disease. These aren’t just background factors-they directly interfere with healing. Diabetics have sluggish blood flow and weak immune responses. Smokers have less oxygen in their blood. Malnourished patients don’t have the protein or calories to rebuild tissue. And uremia? It messes with cell function. The good news? Most of these are modifiable. If you’re planning surgery, quitting smoking 4 weeks ahead, controlling blood sugar, and improving protein intake can make a huge difference. One 2022 paper called these factors "modifiable risk factors," and that’s the key phrase: you can fix them. Sirolimus? You can’t. But you can control the rest.

Timing Matters More Than You Think

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule for when to start sirolimus. The old advice was: wait two weeks. But newer data suggests that’s too cautious for many patients. The American Society of Transplantation updated its guidelines in 2021 to say: tailor it. For a kidney transplant patient with no diabetes, normal BMI, and a clean surgical site? Starting sirolimus on day 5 might be fine. For someone with a BMI over 35, poorly controlled diabetes, and a large abdominal incision? Wait until day 14, maybe longer. What’s changing is the focus on context. A small skin biopsy? Lower risk. A liver transplant with a 12-inch incision? High risk. Also, dose matters. Studies show that keeping sirolimus trough levels below 4-6 ng/mL in the first 30 days reduces complications without losing immunosuppression. That’s a sweet spot many centers are now targeting. It’s not about avoiding the drug-it’s about dosing it smartly.

How Other Drugs Make Things Worse

Sirolimus doesn’t work alone. Most transplant patients are on a mix of drugs: steroids, mycophenolate, tacrolimus, even antithymocyte globulin. And guess what? Most of them also slow healing. Steroids weaken collagen. Mycophenolate stops cell division. Tacrolimus can cause nerve damage that masks early signs of infection. So when a wound doesn’t heal, it’s rarely just sirolimus. It’s the combo. That’s why some patients do fine on sirolimus alone but crash when you add steroids. The key is to look at the whole picture. If you’re going to use sirolimus, try to minimize other healing blockers. Use the lowest steroid dose possible. Avoid antithymocyte globulin unless absolutely necessary. And if you can delay mycophenolate until after the first week, that helps too. It’s not about picking one drug-it’s about managing the whole cocktail.

Why Doctors Still Use Sirolimus Despite the Risks

If sirolimus slows healing, why use it at all? Because it has perks no other drug can match. First, it doesn’t hurt the kidneys. Tacrolimus and cyclosporine? They’re great at preventing rejection-but they slowly destroy kidney function over time. For transplant patients who already have one failing kidney, that’s a nightmare. Sirolimus avoids that. Second, it lowers cancer risk. Transplant patients are 2-4 times more likely to get skin cancer, lymphoma, or other tumors. Sirolimus has actual anti-cancer effects. A 2022 study showed kidney transplant patients on sirolimus had 30-50% fewer malignancies over 5 years than those on calcineurin inhibitors. That’s huge. Third, it reduces viral infections like CMV and BK virus. So even though it’s a healing slow-downer, it’s a long-term protector. For patients with high cancer risk, poor kidney function, or a history of viral infections, the trade-off is worth it. The goal isn’t to avoid sirolimus-it’s to use it for the right people at the right time.

What You Can Do Before Surgery

If you’re scheduled for surgery and on-or might be started on-sirolimus, here’s your action plan:

- Stop smoking at least 4 weeks before surgery. Even cutting back helps, but quitting is non-negotiable.

- Control your blood sugar. If you’re diabetic, aim for HbA1c under 7%. Work with your doctor to adjust meds if needed.

- Boost protein intake. Aim for 1.2-1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily. Eggs, lean meat, dairy, lentils-these are your friends.

- Check your BMI. If you’re overweight, even losing 5-10% of your weight before surgery can cut your complication risk in half.

- Ask about drug timing. Don’t assume sirolimus will be held for two weeks. Ask your transplant team: "What’s our plan for starting sirolimus after my surgery?" and "What’s my target trough level?"

What the Latest Research Says

The old idea that sirolimus always causes bad wounds? That’s fading. A 2022 Wiley publication called those fears "old myths"-and they’re right. More recent studies, including the Mayo Clinic’s 2008 work and newer data from academic centers, show that with careful patient selection and proper dosing, wound complications can be managed. Some centers now start sirolimus as early as day 3 in low-risk patients, with no increase in problems. Others use weekly wound checks and early intervention if signs of poor healing appear. The big shift? From blanket avoidance to personalized risk management. We now know that sirolimus doesn’t cause wounds to fail-it just makes them more vulnerable to other risks. Fix those risks, and the drug becomes safe. That’s the new reality.

Looking Ahead: What’s Next?

The future of sirolimus in transplants isn’t about avoiding it-it’s about using it smarter. Researchers are testing real-time monitoring of sirolimus levels in wound fluid, not just blood. Early data shows wound levels are 2-5 times higher than in blood, which explains why healing is so affected locally. If we can track those levels, we might be able to adjust doses daily during recovery. Also, new formulations are being tested-topical sirolimus for skin cancers, or slow-release patches that avoid systemic exposure. And more studies are looking at combining sirolimus with growth factors or stem cell therapies to counteract its healing effects. The goal isn’t to stop using it. It’s to make sure patients get its benefits without the cost.

Jennifer Patrician

December 6, 2025 AT 00:22Mellissa Landrum

December 7, 2025 AT 07:30luke newton

December 7, 2025 AT 19:47Ali Bradshaw

December 8, 2025 AT 07:04an mo

December 9, 2025 AT 07:03aditya dixit

December 10, 2025 AT 11:36Lynette Myles

December 10, 2025 AT 12:39Annie Grajewski

December 11, 2025 AT 23:41Jimmy Jude

December 12, 2025 AT 06:11