Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia: How to Spot and Treat Rising Pain from Pain Medication

Jan, 21 2026

Jan, 21 2026

It’s a cruel twist: you’re taking opioids to ease your pain, but your pain keeps getting worse. No matter how much you increase the dose, it doesn’t help - and now even light touches hurt. This isn’t your condition getting worse. It’s not tolerance. It might be opioid-induced hyperalgesia - a hidden side effect that many doctors miss, and many patients suffer through for months before anyone connects the dots.

What Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) happens when long-term opioid use makes your nervous system more sensitive to pain instead of less. It’s the opposite of what you’d expect. Opioids are supposed to block pain, but in some people, they end up turning up the volume on pain signals. This isn’t rare. Studies show 2% to 15% of people on chronic opioid therapy develop it. In some clinics, it’s blamed for up to 30% of cases originally labeled as "tolerance."

Unlike tolerance - where you need higher doses to get the same pain relief - OIH means your pain gets worse when you take more opioids. You might notice pain spreading beyond its original location. A lower back ache starts hurting your legs, hips, even your arms. Normal things - a light blanket, a breeze, a doctor’s touch - suddenly feel painful. That’s called allodynia, and it’s a red flag.

Who’s at Risk?

OIH doesn’t happen to everyone. But certain patterns make it more likely:

- High-dose opioids - especially morphine over 300 mg/day or hydromorphone

- Long-term use - symptoms usually appear after 2 to 8 weeks of daily use

- IV or injectable opioids - they hit the system faster and harder

- People with kidney problems - metabolites build up and can trigger nerve sensitization

Genetics also play a role. Some people have variations in the COMT gene, which affects how their bodies handle pain signals. If you’ve had chronic pain for years and your pain keeps worsening despite higher doses, OIH should be on the list of possibilities.

How Is It Different From Tolerance or Withdrawal?

Many doctors confuse OIH with tolerance. Here’s how to tell them apart:

| Feature | Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia | Tolerance | Withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain changes with dose | Pain gets worse when opioid dose increases | Pain stays the same; higher dose needed for same relief | Pain spikes when dose is reduced or missed |

| Pain location | Becomes diffuse, spreads beyond original site | Stays in original area | Often generalized, but improves with dose |

| Allodynia | Common - light touch hurts | Rare | May occur, but temporary |

| Response to dose reduction | Pain improves | Pain returns or worsens | Pain worsens temporarily |

| Timeframe | Develops over weeks of continuous use | Builds gradually over months | Appears within hours of last dose |

Withdrawal causes pain too - but it’s short-lived and tied to missing a dose. OIH is ongoing and gets worse with more medication. That’s why blindly increasing the dose is the worst thing you can do.

How Doctors Diagnose It

There’s no single blood test or scan for OIH. Diagnosis is clinical - based on history and patterns. A doctor will ask:

- Has your pain gotten worse even though you’re taking more opioids?

- Is the pain spreading to areas that never hurt before?

- Do you hurt from things that used to feel fine - like clothing or a gentle touch?

- Have you tried lowering your dose before? Did your pain improve?

There’s also a tool called the Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ). In a 2017 study, it correctly identified OIH in 85% of cases. It’s not perfect, but it helps structure the conversation.

Some clinics use quantitative sensory testing - measuring how sensitive your skin is to heat, cold, or pressure before and after opioid dosing. If your pain threshold drops after taking opioids, that’s a strong sign of OIH. But this isn’t widely available outside research settings.

How to Treat It

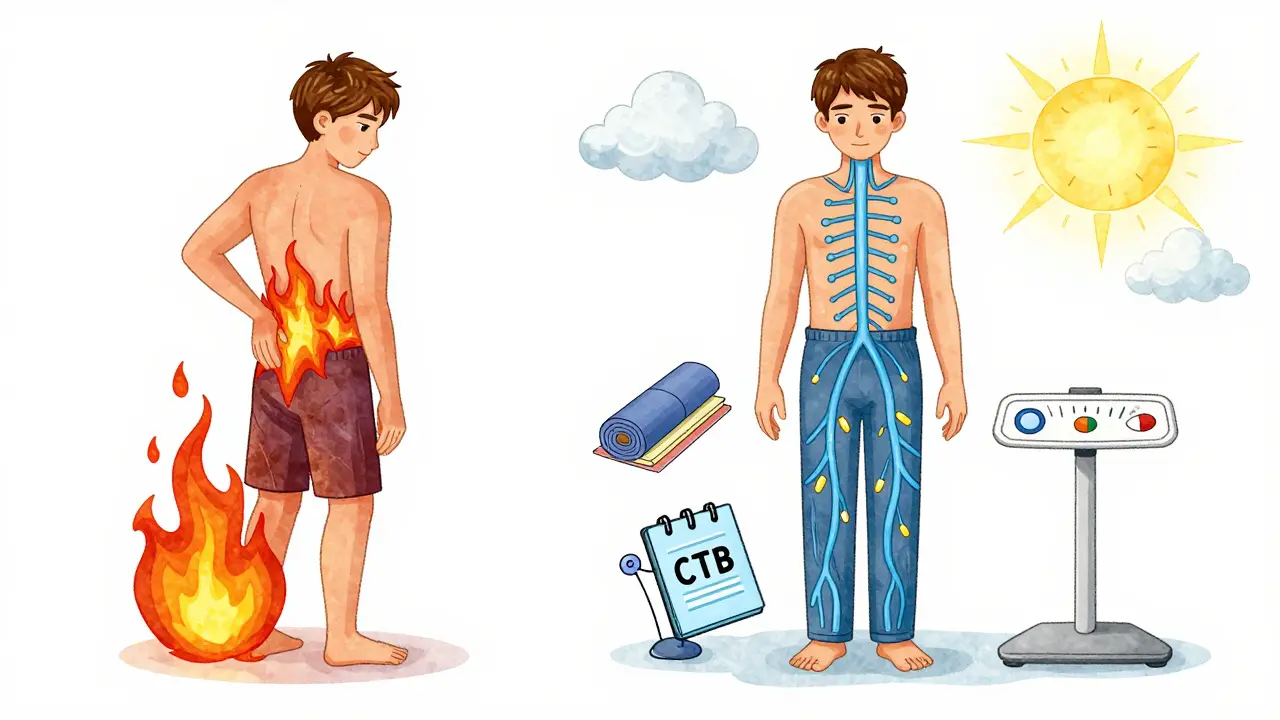

The first rule: don’t give more opioids. That’s like pouring gasoline on a fire.

There are three main strategies:

- Reduce the opioid dose - slowly. A 10% to 25% reduction every 2 to 3 days is typical. Pain may spike at first - that’s normal. Most patients see improvement in 2 to 4 weeks, with full relief by 4 to 8 weeks.

- Switch opioids - not all opioids are the same. Methadone is often chosen because it blocks NMDA receptors, the same ones involved in OIH. Buprenorphine is another good option - it has a ceiling effect and less risk of sensitization.

- Add an NMDA blocker - ketamine, even in low doses, can reverse OIH. A typical dose is 0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg per hour via IV, usually in a monitored setting. Oral ketamine or nasal sprays are being studied, but aren’t standard yet.

Other helpful medications include:

- Clonidine (0.1-0.3 mg twice daily) - calms overactive nerve signals

- Gabapentin or pregabalin (300-1800 mg daily) - targets nerve hypersensitivity

Non-drug approaches matter too. Physical therapy helps retrain the nervous system. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) reduces fear of pain and breaks the cycle of pain → anxiety → more pain. Mindfulness and graded movement can be powerful.

Why This Matters Now

In 2023, over 191 million opioid prescriptions were filled in the U.S. alone. Around 10.1 million Americans are still on long-term opioids. Even though prescribing has dropped 44% since 2016, millions remain at risk for OIH.

Regulators are catching on. The FDA now requires opioid labels to mention OIH as a possible side effect. Pain fellowships now teach it - 78% include it in training, up from just 30% in 2010. Two genetic tests for OIH risk (linked to COMT gene variants) are expected to launch in mid-2025.

Pharmaceutical companies are investing. Three new drugs targeting NMDA receptors are in late-stage trials. This isn’t just academic - it’s becoming a standard part of pain management.

What to Do If You Suspect OIH

If you’re on opioids and your pain is getting worse, don’t assume it’s just your condition progressing. Ask your doctor:

- Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?

- Can we try reducing my dose slowly to see if my pain improves?

- Are there alternatives to opioids that might help?

- Can we test for nerve sensitivity or try a low-dose ketamine trial?

Many patients resist lowering their dose - they fear the pain will return. But with the right support, most find relief. One patient from Auckland, on long-term oxycodone for back pain, saw her pain drop 60% after switching to buprenorphine and starting CBT. She didn’t need the high dose anymore. She just needed the right treatment.

The Bottom Line

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is real. It’s not a myth. It’s not "all in your head." It’s a biological change in your nervous system caused by the very drugs meant to help you. The good news? It’s treatable - but only if you recognize it.

Don’t keep reaching for higher doses. Don’t assume your pain is worsening because your disease is progressing. Talk to your doctor about OIH. Ask for a dose reduction plan. Explore non-opioid options. Your pain might not need more opioids - it might need a different approach entirely.

Can opioid-induced hyperalgesia happen with low-dose opioids?

Yes, though it’s less common. OIH is more likely with high doses or long-term use, but cases have been reported even with daily doses under 100 mg morphine equivalent. It depends on individual sensitivity, genetics, and how long you’ve been taking opioids. If your pain worsens over time - even on low doses - it’s worth discussing.

Is OIH the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a physical change in pain processing - it happens even in people taking opioids exactly as prescribed. You can have OIH without being addicted, and you can be addicted without having OIH. They’re separate issues.

How long does it take to recover from OIH?

Most people start feeling better within 2 to 4 weeks after reducing their opioid dose. Full recovery can take 4 to 8 weeks, sometimes longer if nerve sensitization has been present for years. Patience and consistent treatment - including non-opioid therapies - are key. Rushing the process can lead to setbacks.

Can I use ketamine at home for OIH?

Low-dose IV ketamine is typically given in a clinic under supervision. Nasal sprays and oral forms are being studied but aren’t yet standard. Home use carries risks - including dissociation, blood pressure changes, and potential misuse. Always work with a pain specialist before trying ketamine.

Are there any new treatments for OIH on the horizon?

Yes. Three drugs targeting NMDA receptors are in Phase II/III trials as of 2024. Genetic tests for COMT variants - which predict OIH risk - are expected to launch in mid-2025. These could help doctors choose safer pain treatments before OIH develops. Research is also exploring how gabapentinoids and alpha-2 agonists can be optimized for OIH.

Why don’t more doctors know about OIH?

It was first documented in the 1970s, but for decades, it was dismissed as "tolerance" or "psychological." Training in pain medicine has improved - 78% of fellowships now teach it - but many general practitioners still aren’t familiar. The biggest barrier is that OIH looks like worsening disease or tolerance. Without specific training or tools like the OIHQ, it’s easy to miss.

If I stop opioids, will my pain go away?

Not necessarily - but your OIH symptoms will. The original pain condition may still be there. That’s why switching to non-opioid treatments like physical therapy, CBT, or nerve-targeting meds is essential. Stopping opioids without a plan can leave you worse off. The goal isn’t just to stop the drug - it’s to rebuild your pain system.

Patrick Roth

January 21, 2026 AT 17:49Okay but let’s be real - this whole OIH thing is just Big Pharma’s way of making doctors feel guilty for prescribing opioids. I’ve seen patients on 5mg oxycodone for five years and their pain didn’t change a bit. Meanwhile, the same people are on gabapentin, CBD oil, and acupuncture like it’s a cult. Wake up. Pain is pain. If it’s worse, it’s because the injury got worse or they’re depressed. Don’t invent new syndromes to avoid accountability.

Liberty C

January 22, 2026 AT 16:36Let me break this down for the uninitiated - because clearly, most of you haven’t read the actual neurophysiology papers. OIH isn’t a ‘syndrome’ - it’s a documented NMDA receptor upregulation in the dorsal horn, mediated by glial activation and dynorphin release. The 2017 OIHQ validation study? Flawed. Small sample, no control for psychosocial confounders. And don’t get me started on ketamine - you’re talking about a Schedule III dissociative with a half-life that turns patients into confused toddlers for hours. This isn’t medicine. It’s neurochemical roulette. If you’re prescribing opioids past 90 days without a functional capacity evaluation, you’re not a clinician - you’re a drug distributor with a license.

shivani acharya

January 22, 2026 AT 23:12Oh wow so now the government and Big Pharma are secretly turning our nerves into pain antennas so we’ll keep taking pills and not ask why our bodies are falling apart? 😂 I’ve been on 120mg oxycodone for 7 years because my spine is crushed from a car wreck - but now you’re telling me the pills are making me feel like someone’s grinding glass under my skin? And the doctor just says ‘take more’? Yeah right. I’ve seen the ads - ‘Opioids are safe if used properly’ - and now this? It’s all a lie. They don’t care if you’re in agony. They care about the profit margin. And now they want to give us ketamine? That’s the party drug they used to lock people up for! This is a cover-up. They’re scared we’ll find out the whole pain industry is built on lies. I’m not taking another pill until they prove it’s not poisoning me.

Lauren Wall

January 24, 2026 AT 07:07My cousin was misdiagnosed with OIH for 18 months. They kept increasing her dose. She cried every time her husband hugged her. Then they tapered her off - pain dropped 70% in three weeks. No magic. Just common sense. Stop giving opioids to people who don’t need them.

Ryan Riesterer

January 24, 2026 AT 14:15Neuroplasticity-driven central sensitization is well-documented in chronic opioid exposure. The NMDA-mediated wind-up phenomenon is consistent with animal models and human quantitative sensory testing. The clinical challenge lies in differentiating OIH from neuropathic progression or comorbid psychological amplification. The OIHQ has moderate sensitivity (0.85) but poor specificity (0.62) without corroborative biomarkers. Current clinical guidelines (CDC, 2022) recommend cautious tapering + multimodal adjuvants (clonidine, gabapentin) as first-line. Ketamine infusion remains investigational outside controlled settings.

Mike P

January 25, 2026 AT 16:40Y’all are overcomplicating this. If your pain gets worse when you take more pills, you’re not broken - you’re addicted. Plain and simple. The system wants you to think it’s some fancy science thing so you don’t feel guilty. But let me tell you - I’ve seen guys on 400mg morphine a day who just want to feel good, not be pain-free. They’re not sick. They’re hooked. And now we’re giving them ketamine infusions like it’s a spa day? This country’s gone soft. You want relief? Get off the pills. Work out. Stop whining. Pain is a signal. Not a life sentence.

Jasmine Bryant

January 27, 2026 AT 12:47Wait so if I'm on 80mg oxycodone daily and my knees hurt more now than when I started… and my arms are sensitive to touch… and my doc says ‘increase to 120’… that’s not tolerance? That’s OIH? I think I might have this. I’ve been scared to say anything because I thought I was weak. But this article sounds like me. I’m gonna ask my pain doc about the OIHQ next visit. Thank you for writing this - I didn’t know I wasn’t crazy.

Brenda King

January 27, 2026 AT 13:00I’m so glad this is getting talked about. I’m a physical therapist and I’ve seen so many patients who were told ‘your pain is in your head’ - when really, their nervous system was screaming from too much opioid exposure. One woman, 62, on 200mg morphine for 5 years - couldn’t wear socks without crying. After a 20% taper + CBT + aquatic therapy? She started gardening again. No magic. Just science. And compassion. Please don’t let anyone tell you you’re weak for needing help to get off opioids. You’re brave for even asking.

Keith Helm

January 27, 2026 AT 17:19Per FDA labeling requirements, opioid prescribing must include acknowledgment of opioid-induced hyperalgesia as a potential adverse effect. Clinicians are advised to implement dose reduction protocols in patients exhibiting diffuse allodynia and paradoxical pain escalation. Failure to do so constitutes deviation from the standard of care. Documentation of patient education and alternative modalities is mandatory.