International Generic Drug Prices: How U.S. Costs Compare Globally

Feb, 17 2026

Feb, 17 2026

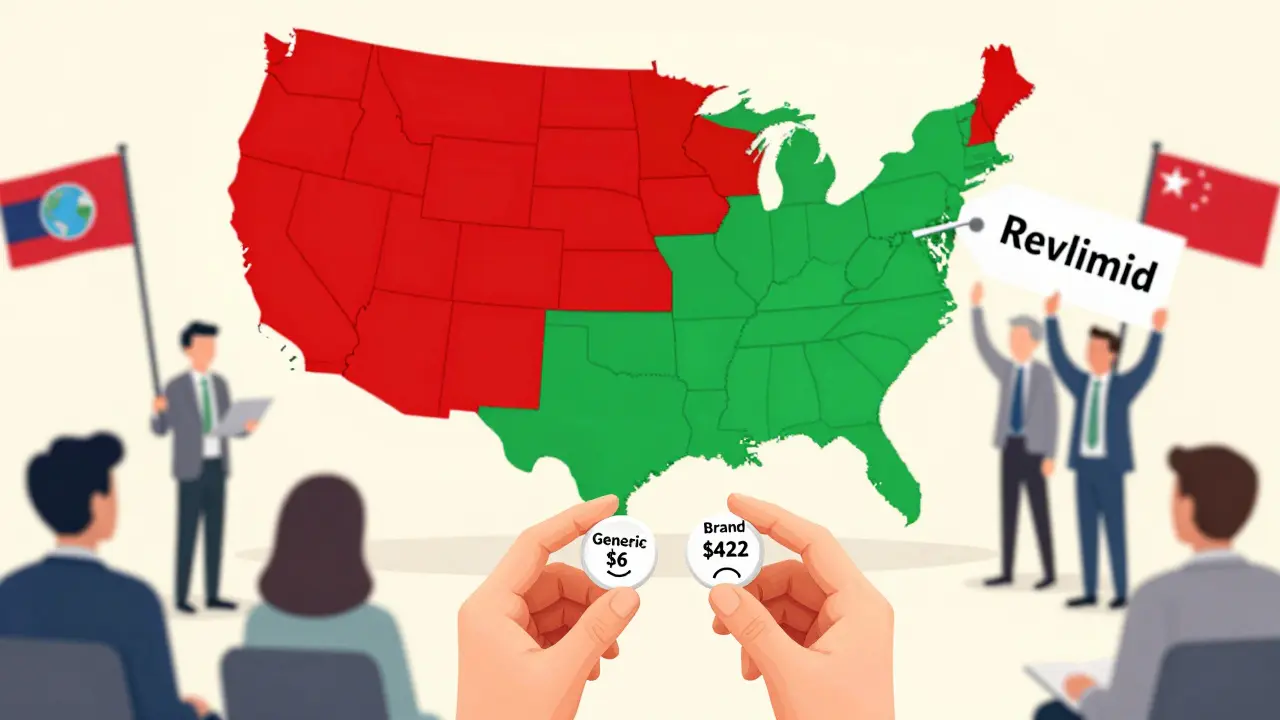

When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and pick up a generic pill, you might think you’re getting a bargain. And for once, you are. But here’s the twist: while the U.S. pays way more for brand-name drugs than almost any other country, it actually pays less for generics. That’s not a typo. It’s the hidden truth behind global drug pricing.

Why U.S. Generic Drugs Are Cheaper Than Elsewhere

In the U.S., about 90% of all prescriptions filled are for generic drugs. That’s not because Americans are more health-conscious - it’s because generics here are dirt cheap. According to a 2022 RAND Corporation study, U.S. prices for unbranded generics are 33% lower than the average in 33 other developed nations. In places like France, Japan, and Germany, the same generic pill can cost 50% more. Why? Because the U.S. has more competition.

When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, dozens of manufacturers rush to make copies. The FDA approves these generics quickly, and they flood the market. When two or three companies start selling the same drug, prices drop by half. With four or more, they crash to just 15-20% of the original brand price. That’s why a 30-day supply of generic lisinopril (a blood pressure pill) costs $4 in the U.S., but $12 in Canada and $18 in Germany.

It’s not magic. It’s math. More competitors = lower prices. The U.S. has more generic manufacturers than any other country. And because Medicare and Medicaid buy in bulk, they can demand even lower prices. In fact, a 2024 University of Chicago study found that after rebates and discounts, U.S. public-sector net prices for generics are 18% lower than in Canada, Germany, and the U.K.

The Brand-Name Price Gap Is Staggering

But here’s where things get ugly. While generics are cheaper, brand-name drugs in the U.S. cost nearly four times more than elsewhere. A 2023 report from the Department of Health and Human Services showed U.S. brand-name prices are 422% higher than the OECD average. That means if a heart medication costs $100 in Japan, it’ll cost $422 in the U.S. before insurance.

Take Jardiance, a diabetes drug. In Australia, the monthly cost is $52. In the U.S., Medicare negotiated a price of $204 - still less than what private insurers charge, but still nearly four times the global average. Stelara, used for psoriasis and Crohn’s disease, costs $2,822 abroad on average. In the U.S., Medicare pays $4,490. That’s not inflation. That’s a system designed to let American patients subsidize drug research for the rest of the world.

The reason? Other countries control prices. Canada, France, and the U.K. have government agencies that set maximum prices. If a drug is too expensive, they won’t cover it. The U.S. doesn’t do that. Insurers negotiate individually. Hospitals negotiate. Pharmacies negotiate. But no one has the power to say, “This is the highest price we’ll pay.” So drugmakers charge what they can - and Americans pay the difference.

How Medicare’s Negotiations Are Changing the Game

In 2022, Congress gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for the first time. It started with 10 drugs. By 2025, it’s expanded to 15. The results? Lower prices - but still way above global averages.

For example, Medicare negotiated a price of $3,200 for the cancer drug Revlimid. In Germany, the same drug costs $1,800. In Japan, it’s $1,400. Even after negotiation, U.S. prices are still 1.5 to 4 times higher than in peer countries. That’s because Medicare can’t force manufacturers to lower prices - they can only refuse to pay for them. And drugmakers know: Americans have nowhere else to go. So they hold firm.

Still, the impact is real. The FDA estimates that the 773 generic drugs approved in 2023 alone will save Americans $13.5 billion over the next few years. That’s not just savings - it’s access. People who couldn’t afford $500 a month for a brand-name drug now get the same active ingredient for $6.

Why Some Generics Suddenly Become Expensive

Not all generics stay cheap. Sometimes, a drug that’s been priced at $3 for years suddenly jumps to $50. Why? Because the market collapsed.

When a generic drug has too many manufacturers, profits get squeezed. Some companies go out of business. Others stop making it. Soon, only one or two suppliers remain. That’s when prices spike. In 2021, a generic antibiotic called doxycycline jumped from $20 to $1,800 per bottle because only two companies were left making it. The FDA documented 16 cases like this in 2023 alone.

This isn’t random. It’s a flaw in the system. The U.S. relies on market competition to keep prices low. But if competition disappears - even for a few months - prices explode. That’s why regulators are now watching how many manufacturers make each generic drug. If fewer than three are producing it, they start looking for ways to bring more in.

What This Means for You

If you take generic drugs, you’re winning. The average U.S. generic copay is $6.16. The average brand-name copay? $56.12. That’s nearly ten times more. And 93% of generic prescriptions cost under $20. For most people, the system works.

But if you need a brand-name drug - especially for chronic conditions like cancer, multiple sclerosis, or rheumatoid arthritis - you’re in trouble. You’re paying the difference between what the rest of the world pays and what the U.S. system allows. And that gap isn’t shrinking. In fact, it’s widening.

The U.S. doesn’t have the highest drug prices because it’s greedy. It has them because it’s the only major country that doesn’t regulate prices. Other nations pay less because they say no. The U.S. says yes - to everything. And that means American patients are footing the bill for global drug innovation.

What’s Next? The Global Ripple Effect

There’s a growing push to fix this. The U.S. government has started pushing other countries to pay more. In 2025, the Biden administration signed an agreement with Pfizer to lower U.S. prices - but only if Pfizer agrees to raise prices elsewhere. The idea? If the U.S. pays less, then other countries must pay more to keep drug companies profitable.

It’s controversial. Critics say it’s unfair to force poorer countries to pay more. Supporters argue that if the U.S. doesn’t pay high prices, no one will fund new cancer drugs or Alzheimer’s treatments.

The truth? It’s a system built on imbalance. The U.S. pays too much for brands. But it pays too little for generics. And that’s why Americans get the best of both worlds - if they’re lucky enough to need a generic.

Tommy Chapman

February 17, 2026 AT 17:00Maddi Barnes

February 18, 2026 AT 22:23Irish Council

February 20, 2026 AT 16:11Jayanta Boruah

February 22, 2026 AT 07:22Hariom Sharma

February 24, 2026 AT 00:15Jana Eiffel

February 24, 2026 AT 22:45Benjamin Fox

February 26, 2026 AT 06:07Robin bremer

February 28, 2026 AT 05:10