HBV DNA Testing: Essential Tool for Managing Chronic Hepatitis B

Oct, 22 2025

Oct, 22 2025

HBV Treatment Decision Calculator

This calculator helps determine if antiviral therapy is recommended based on WHO and AASLD guidelines. Enter your patient's results below:

Key Takeaways

- HBV DNA testing measures the virus’s genetic material, giving the most accurate picture of disease activity.

- Results guide when to start, switch, or stop antiviral therapy, especially with drugs like Tenofovir.

- Combine DNA levels with ALT, HBsAg, and HBeAg for a complete management strategy.

- International guidelines (WHO, AASLD) recommend testing at diagnosis, before treatment, and every 3‑6 months during therapy.

- Understanding test limits - detection thresholds, sample handling, and cost - avoids misinterpretation.

Why HBV DNA testing is a game‑changer in chronic hepatitis B care

When a patient first learns they carry the hepatitis B virus, the next question is usually "how bad is it?" Traditional markers like ALT or HBsAg give clues, but they can be misleading. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) DNA testing quantifies the actual viral particles circulating in the blood, providing a direct measurement of viral replication. That number - called the viral load - tells doctors whether the virus is actively multiplying or sitting quiet, which is the key determinant for treatment decisions.

How the test works: the science behind PCR assay

The most common method is quantitative real‑time polymerase chain reaction (real‑time PCR). A tiny blood sample is taken, the DNA is extracted, and specific HBV genetic sequences are amplified. The machine counts how many copies it sees and reports the result in international units per milliliter (IU/mL). Modern platforms have detection limits as low as 10‑20 IU/mL, meaning they can spot even minimal viral activity.

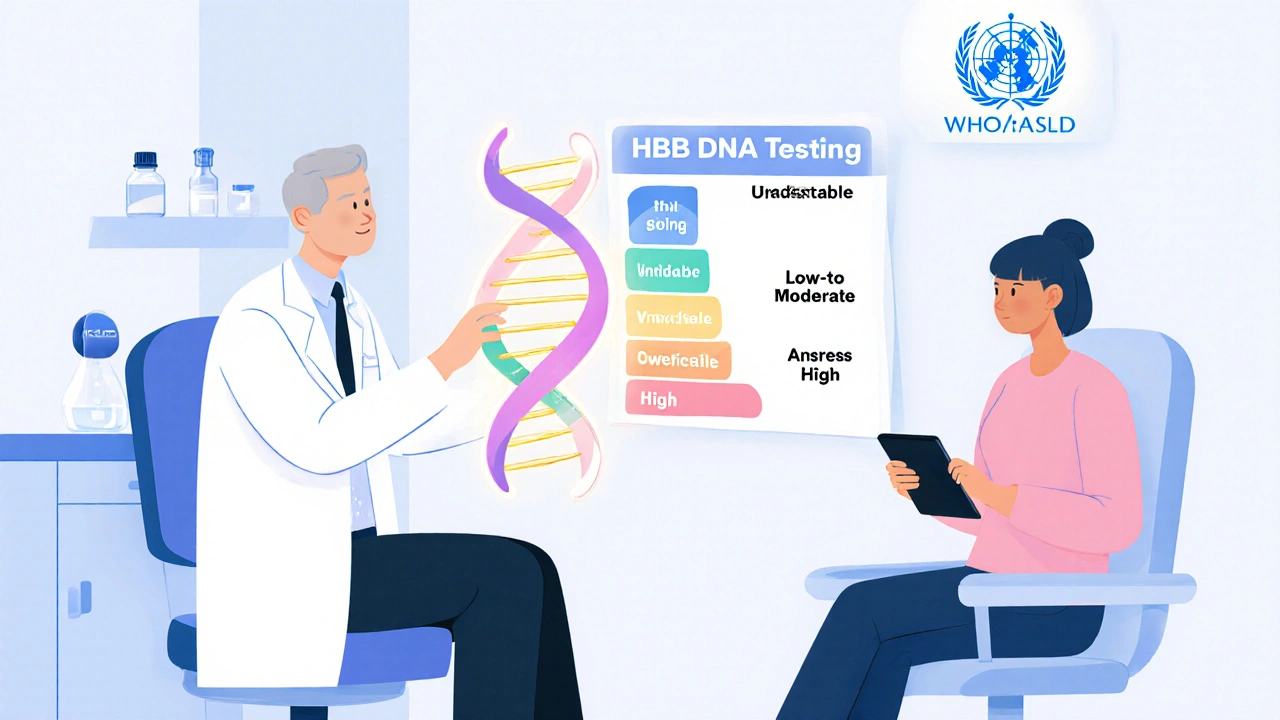

Interpreting the numbers: what does a viral load really mean?

Clinicians use three broad categories:

- Undetectable - the test reads below the limit of detection (usually < 20 IU/mL). This suggests excellent suppression, often seen after consistent antiviral therapy.

- Low‑to‑moderate - 20 - 2,000 IU/mL. The virus is present but not aggressively replicating. Some patients can remain in this zone without treatment if ALT is normal and there are no signs of liver damage.

- High - >2,000 IU/mL. Persistent high levels signal active replication and increase the risk of liver inflammation, fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.

These thresholds align with most international guidelines, but they are always considered alongside other markers.

From test to therapy: when to start antiviral therapy

Guidelines such as those from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend treatment when:

- HBV DNA > 20,000 IU/mL (or >2,000 IU/mL for patients with cirrhosis) and

- ALT is elevated (usually >2× upper limit of normal) or

- There is evidence of liver fibrosis on imaging or biopsy.

First‑line drugs, notably Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), have a high barrier to resistance and can reduce HBV DNA to undetectable levels in >90% of patients within a year.

Integrating DNA results with other markers

Relying on a single test is risky. A typical monitoring panel includes:

| Marker | What it measures | Typical use |

|---|---|---|

| HBV DNA | Quantity of viral genetic material (viral load) | Decides treatment initiation, monitors therapy effectiveness |

| ALT | Liver enzyme indicating inflammation | Signals liver injury; used with DNA to assess disease activity |

| HBsAg | Presence of surface antigen (infection status) | Identifies chronic infection; quantitative HBsAg can predict seroclearance |

| HBeAg | Secreted antigen linked to high replication | Positive HBeAg often means high DNA levels; seroconversion is a treatment goal |

When DNA is high but ALT remains normal, clinicians may watch closely before starting drugs-especially in younger patients without fibrosis. Conversely, a low DNA level with a sudden ALT spike may hint at an immune flare, prompting re‑evaluation.

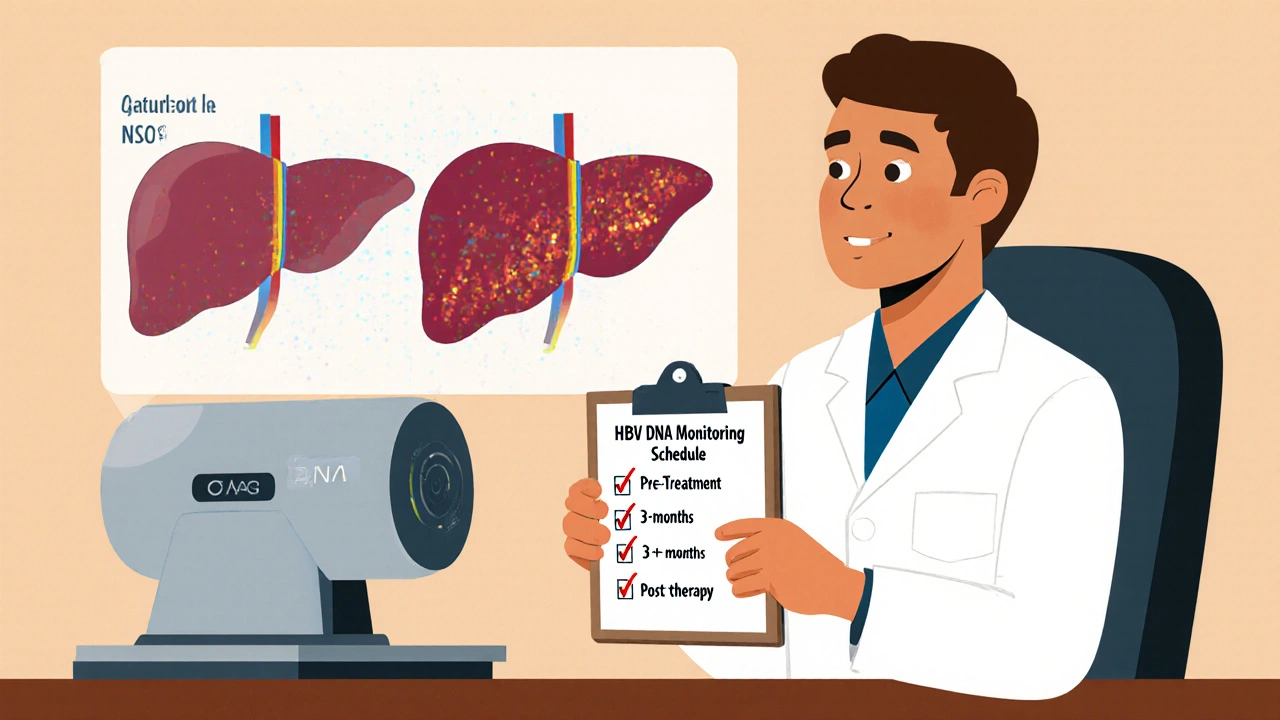

Guideline‑driven timing: when to order the test

Both WHO and AASLD outline a clear testing schedule:

- At diagnosis - Baseline DNA, ALT, HBsAg, HBeAg, and liver imaging.

- Pre‑treatment - Confirm viral load to decide eligibility.

- During therapy - Every 3‑6 months for the first two years, then every 6‑12 months if stable.

- After stopping therapy - Monitor monthly for six months to catch rebound.

These intervals balance the need for early detection of breakthrough replication against cost and patient burden.

Practical considerations: sample handling, cost, and accessibility

Blood is drawn into an EDTA tube, refrigerated (2‑8 °C), and processed within 24 hours. Delays can degrade DNA, causing falsely low results. In many low‑resource settings, point‑of‑care PCR platforms are emerging, dropping the price from US$150-200 per test to under US$50.

Insurance coverage varies. In New Zealand’s public health system, HBV DNA testing is funded for patients meeting WHO criteria; private clinics often charge a flat fee.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

1. Relying solely on a single DNA result. Viral load can fluctuate; always repeat if the result is unexpected. 2. Ignoring assay variability. Different labs report slightly different limits of detection. Use the same lab for serial monitoring when possible. 3. Misreading “undetectable” as cured. The virus can hide in liver cells; treatment must continue as prescribed. 4. Skipping ALT checks. An undetectable DNA with rising ALT may signal an immune‑mediated flare. 5. Over‑testing. Unnecessary repeats add cost without improving care.

Future directions: next‑gen sequencing and quantitative HBsAg

Researchers are exploring ultra‑sensitive next‑generation sequencing (NGS) to detect covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) - the viral reservoir in liver cells. While still experimental, NGS could one day predict relapse risk after stopping therapy.

Quantitative HBsAg, measured in IU/mL, is gaining traction as a surrogate for cccDNA activity. Combined with DNA levels, it may fine‑tune decisions about stopping treatment in low‑risk patients.

Quick checklist for clinicians

- Order HBV DNA at diagnosis, before starting antivirals, and every 3‑6 months during treatment.

- Interpret DNA alongside ALT, HBsAg, HBeAg, and fibrosis stage.

- Use WHO/AASLD thresholds (≥20,000 IU/mL for most, ≥2,000 IU/mL for cirrhosis) to decide on therapy.

- Stick with a single accredited lab for consistency.

- Educate patients that “undetectable” ≠ cured; adherence remains critical.

Frequently Asked Questions

How often should I get my HBV DNA level checked?

If you’re on antiviral therapy, the usual schedule is every 3‑6 months for the first two years, then every 6‑12 months once the viral load is stable. If you’re not yet on treatment, your doctor will check at diagnosis and before any decision to start medication.

Can a low HBV DNA level mean I don’t need treatment?

Not always. Low viral load combined with normal ALT and no liver fibrosis may allow a watch‑and‑wait approach, but each case is weighed against age, family history, and other risk factors.

What does ‘undetectable’ really mean?

It means the test could not find any viral DNA above its detection limit (usually 10‑20 IU/mL). The virus may still be present in the liver, so treatment should continue unless your doctor advises otherwise.

Is HBV DNA testing covered by insurance in New Zealand?

Public health funding typically covers the test for patients who meet WHO treatment criteria. Private patients may need to pay out‑of‑pocket, but many insurers reimburse the cost when a doctor orders it.

What are the main drawbacks of HBV DNA testing?

The test can be expensive, requires good lab infrastructure, and results can vary between platforms. Improper sample handling can also produce falsely low readings.

Sajeev Menon

October 22, 2025 AT 19:56Hey folks, just wanted to chime in and say that HBV DNA testing is really the backbone of chronic hep B management. It gives us a direct look at how many viral copies are cruising around, which is way more reliable than just ALT spikes. When you pair the viral load with HBsAg and HBeAg you get a full picture, kinda like a puzzle. Also, make sure your lab follows the right sample handling – keep the blood cold and get it processed within a day, otherwise you risk a falsely low result. For patients on tenofovir, hitting an undetectable level (<20 IU/mL) usually means the drug is doing its job. Keep the testing schedule tight – at diagnosis, before you start therapy, then every 3‑6 months while on meds. And remember, “undetectable” doesn’t mean the virus is gone, just that it’s below the assay’s threshold. Stay on treatment as prescribed and keep checking those numbers.

Emma Parker

October 27, 2025 AT 18:56OMG totally agree w/ u! I’d add that many clinics still charge too much for the test, so low‑income patients might skip it – that’s a real bummer.

Joe Waldron

November 1, 2025 AT 21:42Indeed, the cost factor is non‑trivial; however, insurers in many regions have started to cover HBV DNA assays, especially when WHO criteria are met, which dramatically reduces the out‑of‑pocket burden; additionally, point‑of‑care PCR platforms are emerging, offering cheaper alternatives without sacrificing sensitivity, thereby expanding access in resource‑limited settings.

Tim Blümel

November 7, 2025 AT 00:29When we talk about HBV DNA quantification, we’re really diving into the heart of viral dynamics 🌟. The viral load tells us not only how many copies are present, but also how the immune system is interacting with the virus at that moment. A rising load can signal an impending flare, while a steady, low level often reflects effective suppression by antivirals. It’s crucial to remember that the assay’s lower limit of detection, usually around 10‑20 IU/mL, sets the floor for what we can confidently call “undetectable” 🚀. This threshold is not a magic cure‑line; the virus can still lurk in hepatocytes as cccDNA, ready to rebound if therapy stops. Therefore, clinicians should pair DNA results with ALT trends, fibrosis assessment, and even quantitative HBsAg when available. In practice, a patient with a viral load of 15 IU/mL and normal ALT is still recommended to stay on tenofovir, because stopping could allow the hidden reservoir to re‑expand. Moreover, the timing of repeat testing matters: checking every 3‑6 months after starting therapy gives a realistic view of viral kinetics. If you see a transient blip-say a jump to 30 IU/mL followed by a drop back to undetectable-don’t panic; it’s often a lab variability issue rather than true breakthrough. Consistency in laboratory choice helps mitigate this, as different platforms may have slightly different calibration curves. From a public‑health perspective, widespread HBV DNA testing enables us to identify candidates for treatment early, reducing transmission rates in the community. As newer, ultra‑sensitive NGS methods evolve, we may soon be able to quantify intra‑hepatic cccDNA directly, which could revolutionize treatment cessation decisions. Until then, the combination of quantitative PCR and clinical judgment remains our best tool. Keep educating patients that “undetectable” is a milestone, not a final destination, and emphasize adherence to maintain viral suppression 😊. Regular follow‑up appointments also give an opportunity to address side effects and reinforce the importance of staying on treatment.

Don Goodman-Wilson

November 12, 2025 AT 03:16Sure, Tim, but let’s be real – most patients just want a cheap pill and forget to show up for every 3‑month lab. All this “philosophical” talk won’t fix the fact that many health systems ignore the cost, leaving people to fund $150 tests out of pocket. 🙄

Diane Thurman

November 17, 2025 AT 06:02The real issue isn’t the price alone; it’s the lack of standardized guidelines in some countries, which leads to inconsistent testing intervals and, frankly, bad patient outcomes.

Iris Joy

November 22, 2025 AT 08:49Great overview, Tim! For anyone juggling therapy, remember that staying on tenofovir for at least a year before considering stopping is a safe bet, and always discuss the plan with your hepatologist.

Sarah Riley

November 27, 2025 AT 11:36Therapeutic inertia undermines viral eradication; adherence optimization is paramount.

Benedict Posadas

December 2, 2025 AT 14:22Yesss! Keep that fire 🔥 burning – staying on track with meds and labs is the only way to win this battle! :)